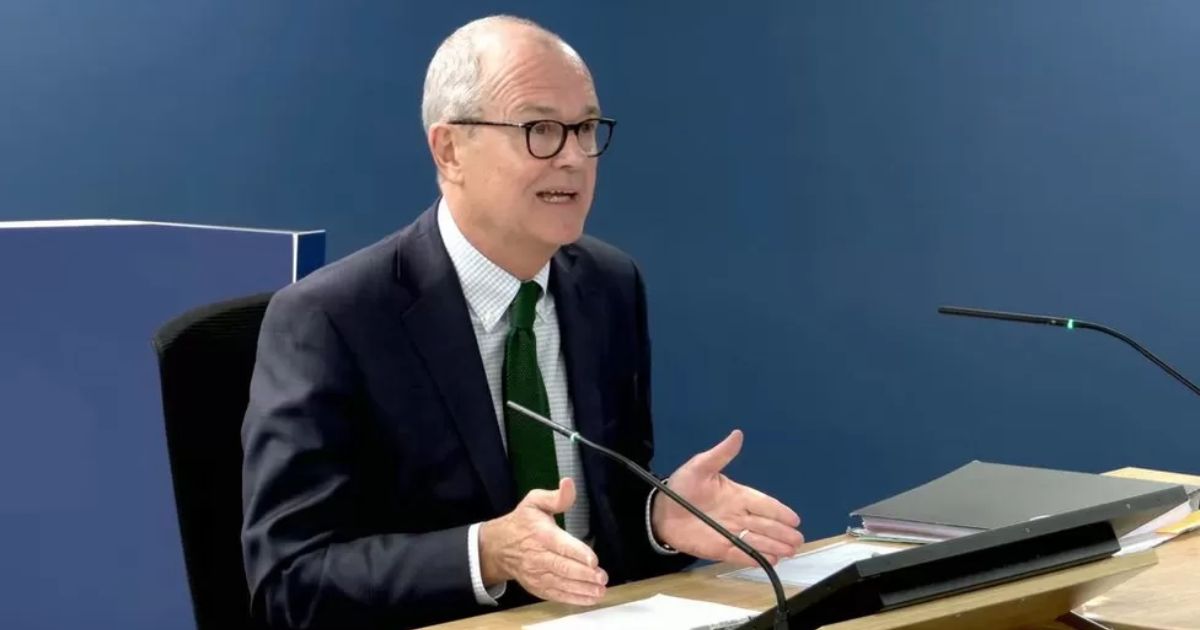

In an astonishing twist, the government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, has revealed that his practice of diary writing during the Covid crisis of 2020 were an unexpected form of mental health protection rather than for publication.

Initially written to relax and deal with stress following arduous days supporting ministers, his unvarnished notes on UK’s response to the pandemic emerged as an important therapeutic rite.

Sir Patrick Vallance is not alone in finding solace in diary writing. In her article on psychotherapy, Julia Samuel gives a big thumbs up to this act.

She states that writing one’s mind like this can be a very good way of releasing emotions just like speaking does.

This also helps to control ones’ emotions; it assists with stress reduction and even strengthens the immune system.

According to Samuel, regardless of whether diarists write their entries for themselves or to be read by others, expressing these feelings through words brings a calming effect.

Perhaps this could mean there are some advantages for those who would like their diary’s entries to be read.

The former medical practitioner Adam Kay admits to a more nuanced shift in his approach to writing upon realizing that a larger audience might have access to his diaries.

However, the quality of his diary writing entries notably elevated with the expectations of publication and unexpectedly their therapeutic efficacy dropped as well.

His initial diary entries, previously essential coping mechanisms in the face of non-stop demands within a hectic professional life, turned into the highly acclaimed book “This is Going to Hurt” and later an award-winning television series.

This evolution demonstrates how adapting content for a wider readership can unintentionally water down the deeply personal catharsis that existed in the original entries.

Diaries have always fascinated public imagination across generations. These include names such as Samuel Pepys, Anne Frank, Alan Clark Tony Benn among others who have left indelible marks through entries in their diaries.

Indeed, even the hypothetical future publication of the late Queen’s personal journal speaks to its perceived importance as pointed out by Travis Elborough in Our History of The 20th Century: As Told in Diaries, Journals and Letters.

Elborough argues that diary writing is not only useful for individuals, but also for society as a whole.

He states that referring to diary writings provide a unique view of past events and fill in gaps left by official records.

Professor Alun Withey from Exeter University highlights the wealth of historical information contained in diaries and their value as primary sources that give glimpses into people’s daily routines and important moments in their lives.

Conversely, Kathryn Carter, an autobiographer and life writer at Wilfrid Laurier University, agrees that there are disadvantages such as pressure to keep up with consistent entries.

Carter maintains that even if they are written for private intentions, diary writings are not inherently private.

On the other hand, Elborough and Withey write about fears of people stumbling upon negative comments about themselves within these books.

Sir Patrick Vallance was clear during the Covid inquiry that his diary played a role in his preparation for the following day.

Nonetheless, inadvertent emergence of his personal ramblings into public domain exposed criticisms against UK government response to pandemic.

The therapeutic touch of diary writing is strongly felt through this offer comfort and relief from mental agony.

Nevertheless, it also underscores the contrast between personal reflection and possible public exposure.

The importance of diaries lies in history and society whereby they provide great insight absent when conventional records are made.

Thus, keeping a diary becomes much more than a simple act of individual catharsis because it helps enrich history so as to teach future generations some lessons based on personal experiences during significant moments in time.